Learning Objectives

- List, compare, & contrast the animal mating systems monogamy, polygamy (polygyny and polyandry), and promiscuity, and recognize examples of animals that use each mating system

- Recognize different ecological factors that characterize different animal mating systems

- Explain relationships between sexual selection, parental investment, and different mating systems

Animal mating systems

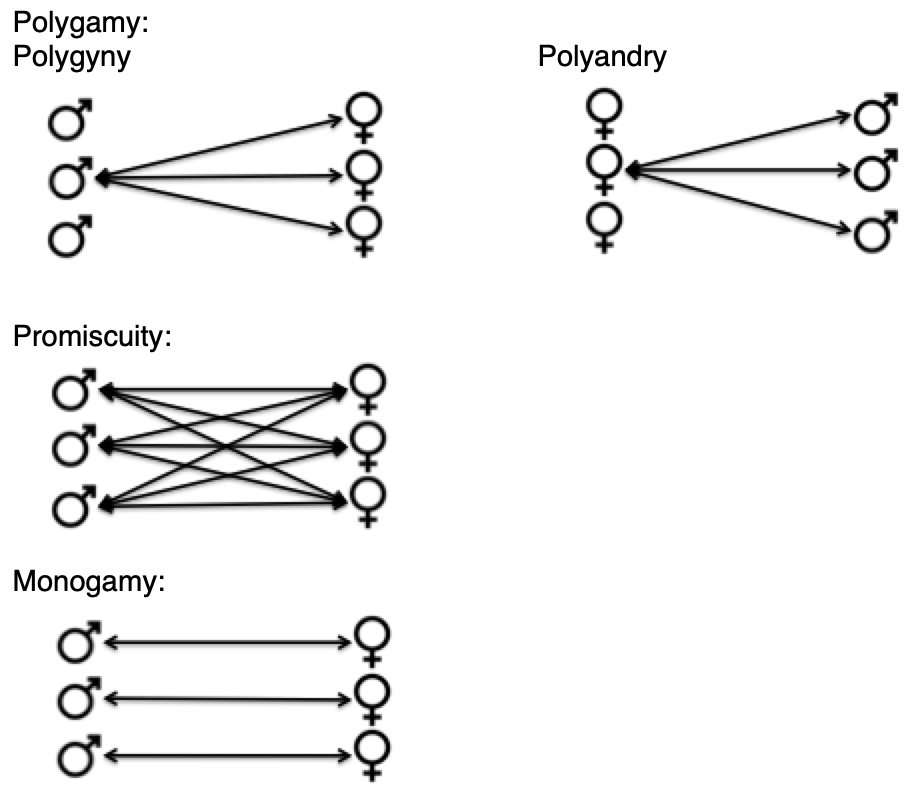

Three general mating systems, all involving innate and evolutionarily selected (as opposed to learned) behaviors, are seen in animal populations: monogamous, polygamous, and promiscuous.

In monogamous systems, one male and one female are paired for at least one breeding season. In some animals, such as the prairie vole, these associations can last much longer, even a lifetime. While there are many non-mutually exclusive hypotheses to explain selection for monogamous mating systems, one prominent explanation is the “male-assistance hypothesis,” where males that remain with a female to help guard and rear their young will have more and healthier offspring. The male-assistance hypothesis is supported by the observation that many monogamous species live in environments with widely scattered resources, meaning that it takes the effort of more than one adult to forage for enough resources to rear the young.

Male and female zebrafinch. Zebrafinches, like many songbirds, exhibit a socially monogamous mating system. Image credit: Keith Gerstung, Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taeniopygia_guttata_-Bird_Kingdom,_Niagara_Falls,_Ontario,_Canada_-pair-8a.jpg

True monogamy, also called sexual monogamy, is where both partners mate only with each other; true monogamy is exceedingly rare. Much more common is social monogamy, where two individuals partner together to rear their offspring, but also engage in “extra-pair copulations,” or matings with other individual (in human social parlance, we would call this “infidelity”). Social monogamy has both advantages and disadvantages for each partner. You can imagine the advantage for a male in this scenario: he helps rear offspring with his social partner, increasing the likely survival of those offspring, but he also mates with other females, thus increasing his total number of offspring (assuming any of these other offspring also survive).

Social monogamy can also be advantageous for the female: she has help from a social partner in raising her offspring, but she can also mate with other males who may be genetically “better.” The disadvantage for the male in this scenario is that he is most likely helping to raise offspring that are not his own. The disadvantage for the female is that the male may abandon her – and her offspring – if he detects that she has mated with another male. The vast majority of songbirds demonstrate social monogamy, where up to 40% of the offspring in a mating pair’s nest were not actually fathered by the male partner.

Polygamy refers to either one male mating with multiple females or one female mates with many males. When one male mating with multiple females, called polygyny (“many females”), the female takes responsibility for most of the parental care as the single male is not capable of providing care to that many offspring. For instance, imagine that a male has established a territory such that he can provide access to resources. Females that enter the territory are drawn to its resource richness, which may signal that he has good genes for protecting a territory. The female benefits by mating with a genetically fit male at the cost of having no male help care for the offspring. For example, in the yellow-rumped honeyguide (a bird) males defend beehives because the females feed on beewax. As the females approach to find beeswax, the male defending the nest will mate with them.

Aside from resources, another type of polygyny is called a lek system. In leks, the species has a communal courting area where several males perform elaborate displays for females, and the females choose their mate from the performing males. Lekking behavior is observed in several bird species including the sage grouse and the prairie chicken.

The other type of polygamy is called a polyandry (“many males”), where one female mates with multiple males. Polyandry very rare because it involves sex role reversal, where females invest less in offspring while males invest more.

Polyandrous mating, in which one female mates with many males, occurs in pipefish. (credit a: modification of work by Brian Gratwicke; credit b: modification of work by Stephen Childs)

Pipefishes, a relative of seahorses, exhibit polyandry where females compete for access to males. In both pipefishes and seahorses, males receive the eggs from the female, fertilize them, protect them within a pouch, and give birth to the offspring (see below). However, seahorses are monogamous, while pipefish are polyandrous.

Why do these similar species differ in mating system? Ecologically, seahorses live in habitats with widely distributed resources, which means that the seahorse population is spread out and spread thin. The scattered population means that it is can be difficult to find a mating partner. Natural selection favors keeping a partner, once found, for reproductive assurance. In contrast to seahorses, pipefish tends to live in very dense populations in resource-rich environments. Because the male’s pouches, rather than the female’s eggs, are the limiting resource in reproduction, females compete with each other for access to males.

Promiscuous mating systems occur when females mate with multiple males, and males mate with multiple females. Promiscuity generally occurs when a single male is unable to sexually monopolize a group of females, either because the females range more widely than the territory size of a single male, so they interact with multiple males (eg, the maximum territory size a male can defend is smaller than the females’ ranges), or because males and females live together in large social groups that a single male cannot monopolize.

In large social groups, often all females are sexually receptive at the same time, meaning that a single male cannot prevent other males from mating with other females while he mates with one female. Because each female mates with multiple males, paternity is never certain. The uncertainty of not knowing “who’s the daddy” selects for males to avoid infanticide, as they may inadvertently kill their own offspring.

The video below provides a quick overview of animal mating systems:

Mating systems are influenced by competition for mates, and competition for mates is influenced by mating system. Except in the case of sexual (true) monogamy, there is always competition for fertilization. What differs in different mating systems is whether the competition occurs before mating (direct male competition) or after mating (sperm competition). In class we’ll spend some time considering the relationships between mating system, when competition occurs, and the resulting effects on an individual’s behavior and/or appearance.

A schematic of the types of animal mating systems. Arrows indicate matings between individuals. Based on Wolff and Macdonald, TRENDS in Ecology and Evolution 2004.